I never expected Coney Island to become a project. It certainly was not supposed to be a book. I went to Brighton Beach for the food and Coney Island for the Friday night summer fireworks. The ocean drew me in. Living in Manhattan I had forgotten what nature smelled like. The sound of the waves and the mist in my face were the calming forces I needed to stay strong. Over time I took a few snapshots – cigarette butts in the sand for my Smokers’ Detritus series or landscape photographs of blowing sand at dusk. And then I began to notice the people. -Paul B. Goode

©Paul B. Goode

It didn’t begin with Coney Island. At first it was about Brighton Beach. I went there for the food. Between 1988 and 1992 I took ten trips to the Soviet Union. I missed the Russian meals a friend’s mother prepared during my stays in Leningrad. I can find those same dishes at the buffets in Brighton Beach. Taking longs walks along the ocean’s edge I breathe in the fresh air and relax to the sounds of the wind and surf. The beach is a one hour subway ride from my Upper West Side apartment. It feels like a completely different world.

I began feeling guilty, these weekday afternoons spent at the ocean, walking from Brighton Beach to Coney Island and back again instead of retouching on the computer or producing my next shoot. I needed an excuse to justify these beach adventures. Previously, my only Coney Island photographs were taken during the once a year Mermaid Parade — an easy place to find great subjects. Now during my walks I began to notice the light. It’s different on the beach. The ocean mist and reflections

off the water create a remarkable glow.

A camera remains in my hand as I walk the wet sand at the water’s edge. I study the light, how if falls both on nature and the people enjoying the beach. I look for subjects to photograph, not the stereotypical Coney Island characters but real people out for a late afternoon stroll. Before me is the melting pot of America, walking the same patch of beach, enjoying their time spent with friends and family. It feels honest. This is real life.

I have visited the beach during every season. Initially I cared more about what remained of nature, things man could not destroy; the water, wind, tides, seaweed, and shells. I watched the beach change shape over time due to the ocean currents and storms. I know the patch of beach that captures my favorite shells. I understand which tide cycle works best for wide-angle landscape photographs. Creating new work is often half science, half art.

©Paul B. Goode

I wander Coney Island for hours, searching for interesting combinations of people within the nature of the beach. A series of sketches appear in front of me, constantly changing as people move in and out of my camera’s view. I watch the landscape, the perspective shifting as I move along the shore. Suddenly everything falls into place and the final work of art appears. I shoot away, hoping I’ll capture the perfect composition of people and place.

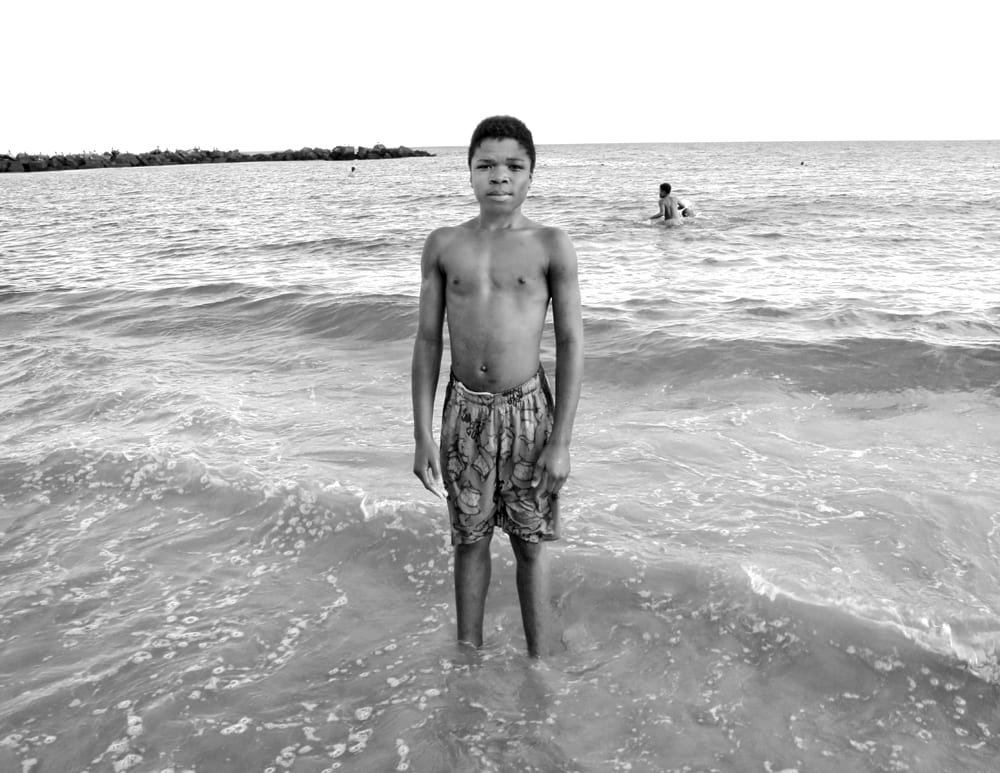

It didn’t happen that way with this young man. He saw me at work, somehow understanding what I searched for. I don’t know how long he watched before approaching me, “You can take my picture if you want.”

It took a few seconds for me to understand what he had said. People rarely speak to me on the beach. If I’m crawling on the ground photographing a cigar butt in the sand, someone might come up and ask what I’m doing. Otherwise I feel invisible.

It felt strange having my protective bubble broken. Instead of floating across the beach unseen I now became one of the masses. I don’t remember if I placed the young man at the spot or if he picked the location himself. I shot 20 images in half a minute, adjusting my composition, waiting for the swimmers in the background to fall into the proper place.

Neither of us said a word during that time. He did understand what I wanted. There was no need for direction.

I imagine I asked his name but it was quickly forgotten. I showed the young man our work on the back of the camera. I know he was proud of his appearance but there was little reaction. I thanked him for his time, climbed back into my protective bubble and continued my journey along the beach.

©Paul B. Goode

The Coney Island Mermaid Parade offers endless photographic opportunities. After the parade the beach and boardwalk fill with swarms of photographers pursuing the Mermaids remaining in the area. It can feel claustrophobic and intense. Not all amateur photographers understand the rules. They are too aggressive, appearing to prey on the scantily clad theme-costumed women. As a professional I do my best to respect everyone’s dignity and space.

I passed Blythe while heading towards a group of mermaids assembled among a cluster of rocks on the water’s edge. Up to that point I hadn’t seen much that inspired me. As I walked by I felt Blythe begging to be photographed, sitting alone, her body in perfect alignment with the Parachute Jump. Blythe, her blanket set up away from all others, sitting cross-legged as if the Queen of the Beach.

Blythe appeared happy in her isolation. A great photograph stood before my eyes. I didn’t want bother her. She seemed at peace in her place.

Blythe was topless

I spent the next few minutes searching for other images along the beach but came up empty. I headed back in the direction of Blythe, once again mesmerized by her presence. This time I couldn’t pass her by. I walked up and quietly asked if I could take her portrait. I knew it wouldn’t be the same image as if I had caught her unaware, natural in this place on the beach; but I had to hav e the picture.

Blythe seemed honored. Her warmth was obvious and genuine. Now having permission I took the time I needed to compose my image, watching people in the background move in and out of the composition. After a few shots I brought the camera up to Blythe, showing her the photographs. She loved them, asking me to join her on the blanket, “Let’s relax together and talk.”

I sat with Blythe for over an hour, ignoring a friend somewhere nearby trying to reach me on the phone. I don’t remember what we spoke about. We laughed. I took more pictures. We both felt as if we had been friends for years. Blythe touched me as she talked. Her skin. I had never felt anything like it. Her touch was soft and cool, reminding me how the sand feels at White Sands National Monument — healing, nurturing, protecting. When I visited White Sands I wanted to lie on the sand forever, letting it envelop me, becoming one with the nature. If was the same with Blythe. I felt safe sitting on her blanket, within her energy bubble. I never wanted to leave her side.

©Paul B. Goode

There are not many beaches in America where you find multitudes of people wandering in the surf late at night. Where I grew up along Lake Michigan you might find a lone jogger. On Venice Beach the local gangs come out at sunset. If you don’t have street smarts that’s the time to return home. I’ve collected seashells by flashlight on Miami Beach not seeing another soul the entire evening.

Coney Island is different. On a hot summer night you can find hundreds of people wandering the beach and boardwalk. It’s not only near the amusement park but along the entire two mile stretch of shore from the Coney Island Pier to the boardwalk’s terminus in Brighton Beach. Misty shadows wander through the surf silhouetted by the bright lights of the amusement park.

The area can feel like an ocean side Times Square; the crowds, the noise, the tourists. The boardwalk and beach near the pier might appear safe but a few of the streets leading away from boardwalk are not. Walking in these areas I have the same feeling I did wandering through Times Square in the early 1980s. After leaving the safety of the beach one always needs to be aware. Sadly pickpockets and muggers are also attracted to the crowded beach, realizing drunk beachgoers heading down the darkened streets towards the metro station make easy targets.

For some reason the possibility of danger doesn’t seem to matter. Most of the people visiting Coney Island at night are true New Yorkers. I imagine we’ve become numb to trouble. Near the Aquarium families sit on the benches, children playing in almost total darkness. Everyone is happy; a dark version of Disneyland.

Passing the Aquarium towards Brighton Beach one mostly hears Russian voices. It does not surprise me to find Russians on the boardwalk at night no matter what the season. I spent a lot of time in Russia. They are sturdier than Americans. You only have to visit their country to understand why. Whether as peasants under the czars, Soviets under Lenin and Stalin, and presently under their new dictator, Vladimir Putin, the Russian people have never known real freedom. Living in America, for the first time they can go wherever they wish, speaking without reprisal.

While photographing in the streets of Leningrad and Moscow I was often mistaken for a KGB agent. People hid their faces until they realized I was an American journalist. Then they welcomed my camera with open arms. I get a similar ‘KGB agent’ feeling while photographing Russian people in Brighton Beach, except rarely the welcome. Instead of embracing the moment or turning away from the camera many become aggressive and angry. I’m told I have no right to take their picture, even after asking for permission. I find it funny and bizarre at the same time. Now that they live in a free society they choose to restrict my freedom to photograph in a public place. Few people outgrow their pasts.

Bio

I bought my first camera at 12 years old. At the time my goal was to document the history of my friends and family. I never stopped taking pictures.

As a photographer I have had the great fortune to blur the lines between art and commercial photography. My assignments have taken me to Red Square, riding on the Orient Express, and climbing the Death Valley Dunes in the August heat. Clients as varied as the American Ballet Theatre, NYU Medical Center, Fizogen Nutrition, and The New York Times have allowed me to create work I would be proud to exhibit in any gallery.

54 years later, 45 years as a professional photographer, my biography could fill a book. No matter the subject, my photographs have always been about capturing the souls of people. Books of my work have been published featuring women bodybuilders, ballerinas, the Soviet Union, and Coney Island. My photographs and publications appear in the collections of The Metropolitan Museum, The Getty Museum, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Houston Museum of Fine Arts.

Equipment: The photographs featured in Coney Island Scrapbook were taken with the Canon 7D Mark II camera using a 17-55mm f2.8 IS lens. The color setting for the photographs is monochrome and the images are shot in RAW. The ISO for the photographs falls within the 1000 – 5000 range. The images are processed using Canon’s Digital Photo Professional software, corrected and retouched in Adobe Photoshop CS4.

I retouch digitally in the same manner I worked in the darkroom, using levels and curves for contrast and density, adjusting certain areas of the photographs with dodge and burn. Very little work is done on the images that could not have been accomplished in the darkroom with the exception of removing pieces of garbage left on the beach by human beings.

Contact info

email: paul@paulbgoode

www.paulbgoode.com www.paulbgoodedance.com @paulbgoode

Book details

Coney Island Scrapbook is 68 pages, 11″ x 8.5″, spiral bound; soft cover. The book features 57 full page photographs along with 11 pages of essays and text.

Signed books may be purchased directly from the photographer for $38 (includes sales tax and shipping by USPS media mail). Venmo, Zelle, and Paypal are accepted. Please email paul@paulbgoode.com to place an order.

Unsigned copies of Coney Island Scrapbook (includes access to a digital copy) may be purchased directly from the distributer for $29.95 plus sales tax and shipping. A digital only version is available for $4.95. The order can be placed at https://www.magcloud.com/browse/issue/1793248.

Nancy McCrary

Nancy is the Publisher and Founding Editor of South x Southeast photomagazine. She is also the Director of South x Southeast Workshops, and Director of South x Southeast Photogallery. She resides on her farm in Georgia with 4 hounds where she shoots only pictures.