Nancy McCrary: Josephine, thank you for talking with us today. You have two books out now that we’d like to know more about today – both must-haves for serious photography book collectors. As always, they are filled with gorgeous images and alluring text, and the books themselves are works of art..

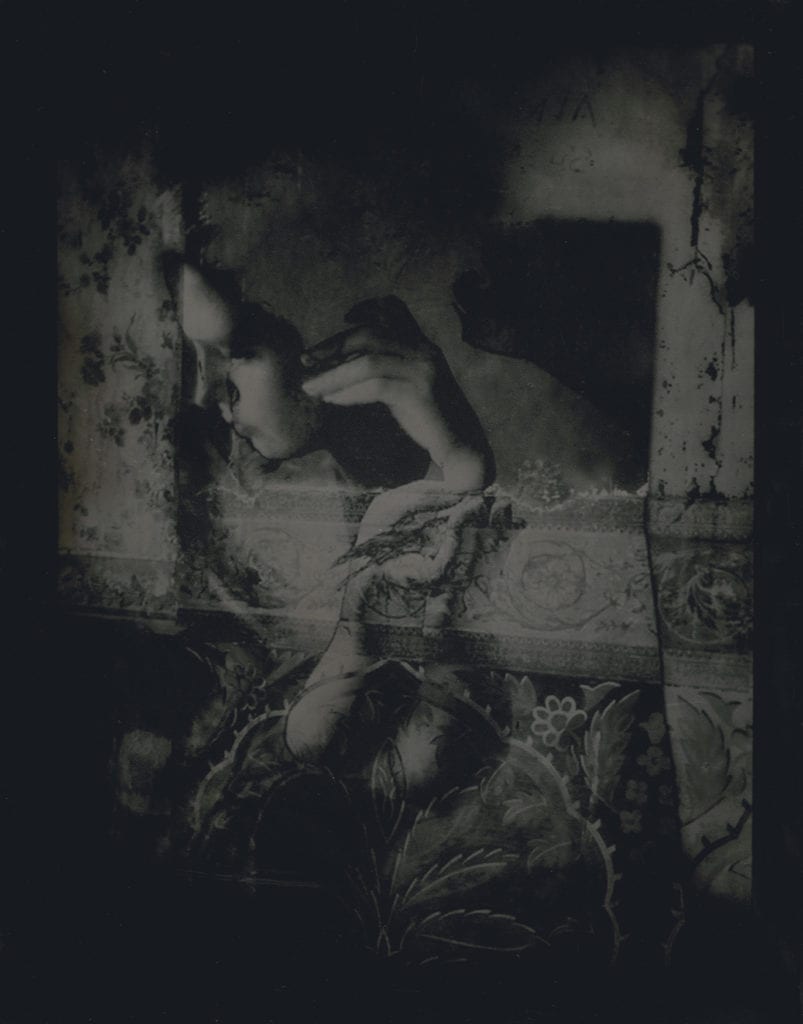

Beyond Thought is a collaboration in a broad sense of the word – you have formed images to accompany the words of Brazilian author Clarice Lispector. How did you find this author, and what so strongly connected you to her writing?

Josephine Sacabo: A friend of mine from Guatemala mentioned her so I bought a book of her selected newspaper columns and I couldn’t believe the scope and depth of the columns- unlike anything we would normally expect to find in a newspaper. She says things like

“what am I doing in writing to you? I’m trying to photograph perfume.”

What an eloquent and beautiful way to express what one is so often attempting to do in art!

NM: You have said the writings of Clarice make you see things you wouldn’t have otherwise noticed. Would you talk about that a bit?

JS: I will never see orchids the same way after reading this line from Clarice . Or listen to music without feeling it has become a part of me.

“I love orchids. They are born already artificial: they are

born already art”

“And as for music, after it’s played where does it go?”

NM: The line, ‘I am an object loved by God’ is so powerful. What did this statement mean to you in the artistic sense, the visualization of it.

JS: “I am an object loved by God “ is probably my favorite line of hers. And the lines that follow “ and that makes flowers blossom upon my breast. He created me the same way I created the sentence I just wrote ‘I am an object loved by God”

She includes the artist in the process of all creation with these lines – we are God’s artwork and he loves us just as we love a photograph or a poem that we create.

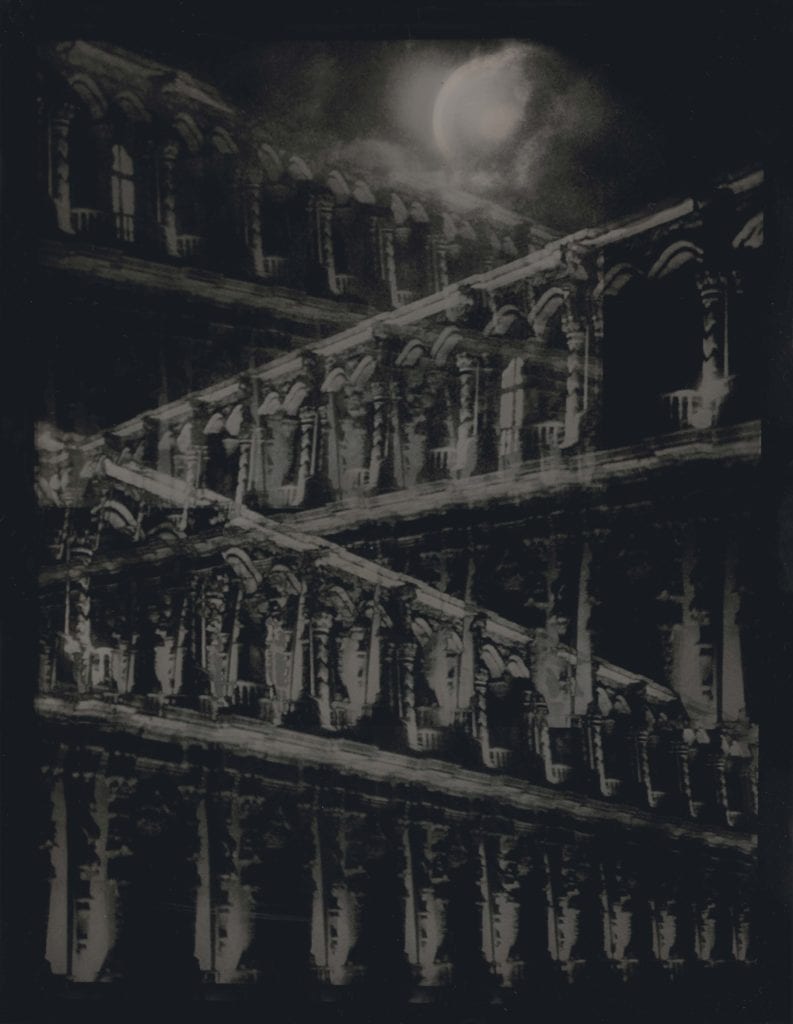

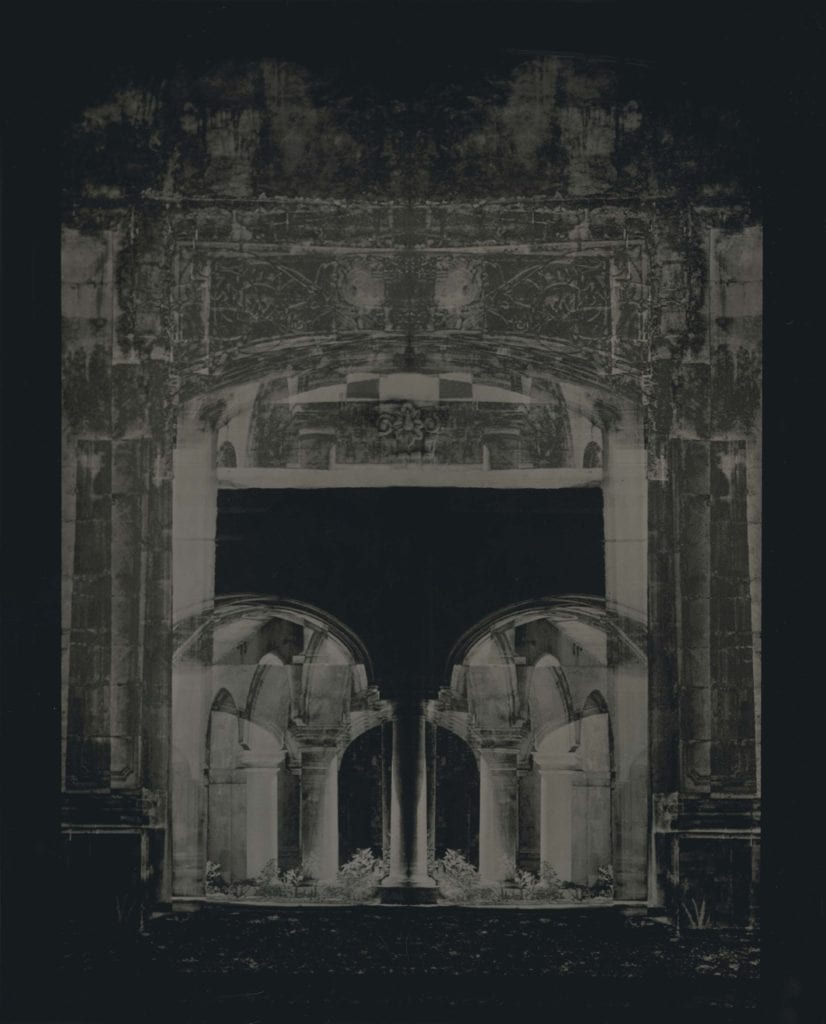

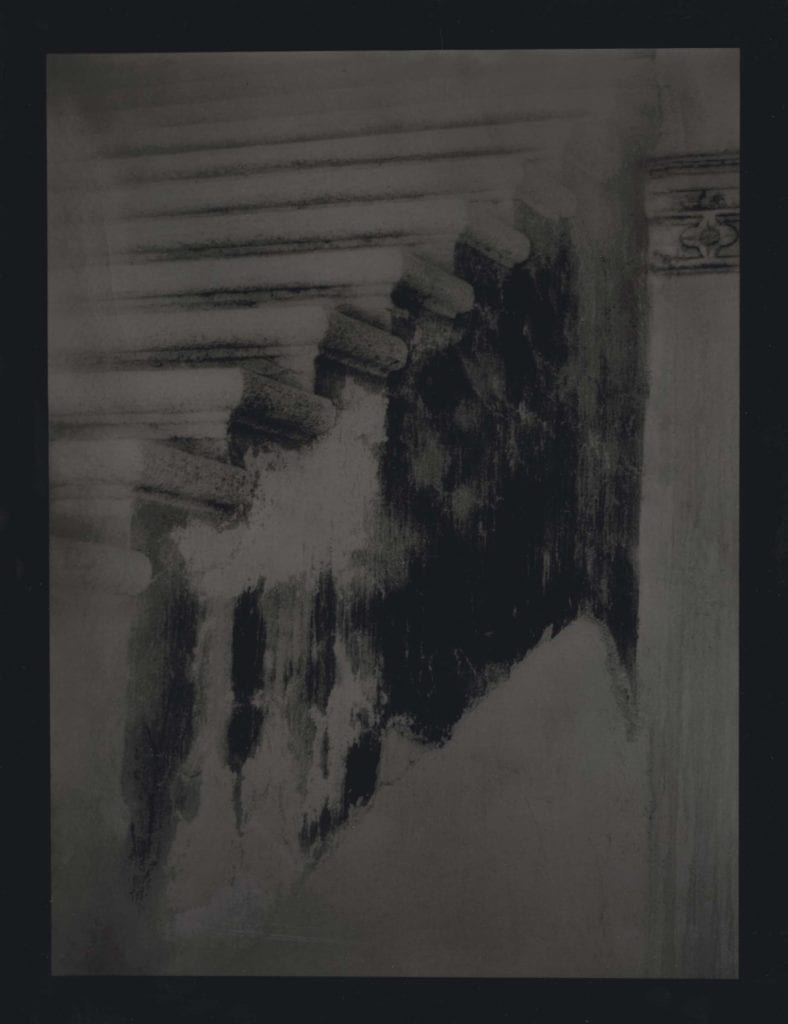

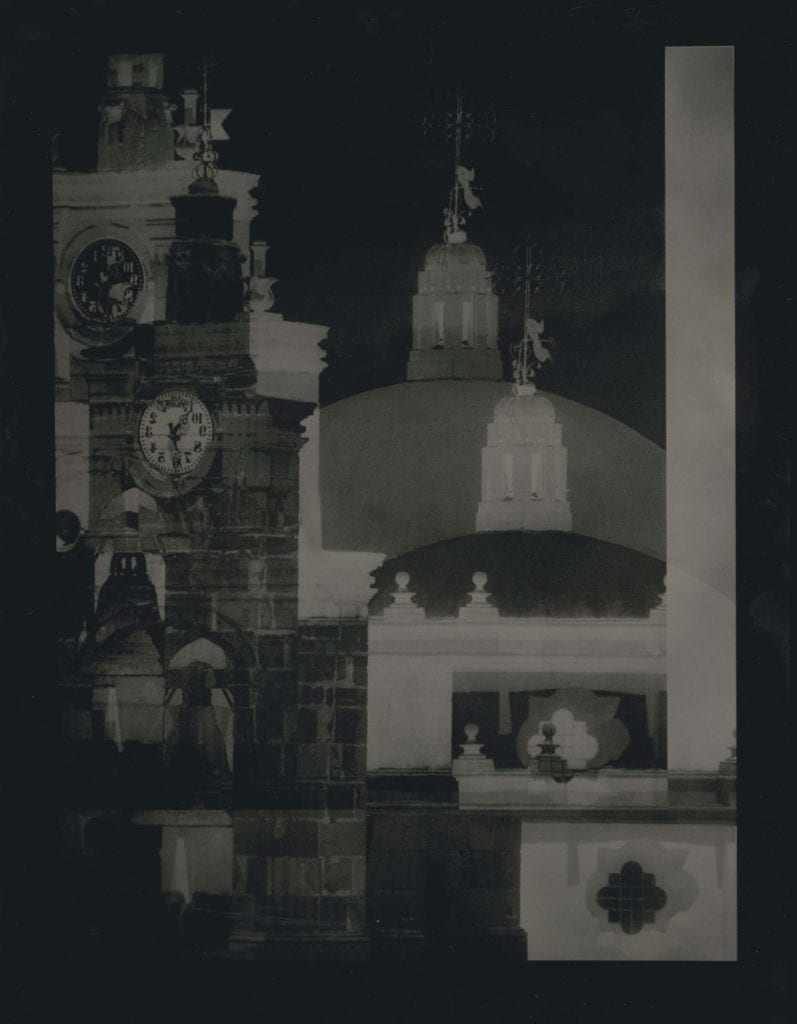

NM: With Lux Perpetua you are inspired again to pair your images with words. This time the voice is that of Sor Juana Ines de la Cruz, a woman whose life was extraordinary – as is yours. Your hope is “that these images will break the silence so that we may once again ‘hear her with our eyes’.” Tell us about discovering her writings and a bit about her. I know dreams play a part in your work, and this is no exception – is there a meditative or other provocative process you used to conjure up the corresponding image in your mind when you read her writings?

JS: Sor Juana is another gem in the history of women artists. To think that she was a feminist advocating the rights of women to study and be treated as equals as a cloistered catholic nun during the Inquisition in Mexico is almost inconceivable. She was a Mozart like prodigy who taught herself to read and write as a very young child and consumed her grandfather’s entire library before she was sent at 13 to Mexico City to live with relatives who could help her continue her studies. There she quickly gained fame for her intelligence and her knowledge to the extent that she was invited to the royal court to debate with professors and philosophers and distinguished herself so completely that the reigning Marquise invited her to become her lady in waiting at the court. She lived for several years as the darling of the court, creating poems, plays, music and studying astrology until the Marquise was to return to Spain. At that point she had no dowry, was in fact a bastard, and had insisted that she would never marry – so she entered the convent thinking that she would be sheltered and could continue her studies, which were her passion in life. The Marquise took a volume of Sor Juanas poems and published them in Madrid where she became something of a sensation. Important intellectuals of the day would come to her cell at the convent which soon became the reigning intellectual salon in the New World. She wrote secular love poetry that is among the most beautiful in the Spanish language. Eventually the Inquisition silenced her. That we know her work today is a miracle really.

Dreams are important to me for the feeling they impart when one remembers them – they’re shrouded in a sort of dejá vu that I find really evocative. Sometimes someone or some place rings that same bell and I know I’m being moved at the deepest part of myself. I have no process to make that happen – its always for me a reaction that feels almost like a memory.

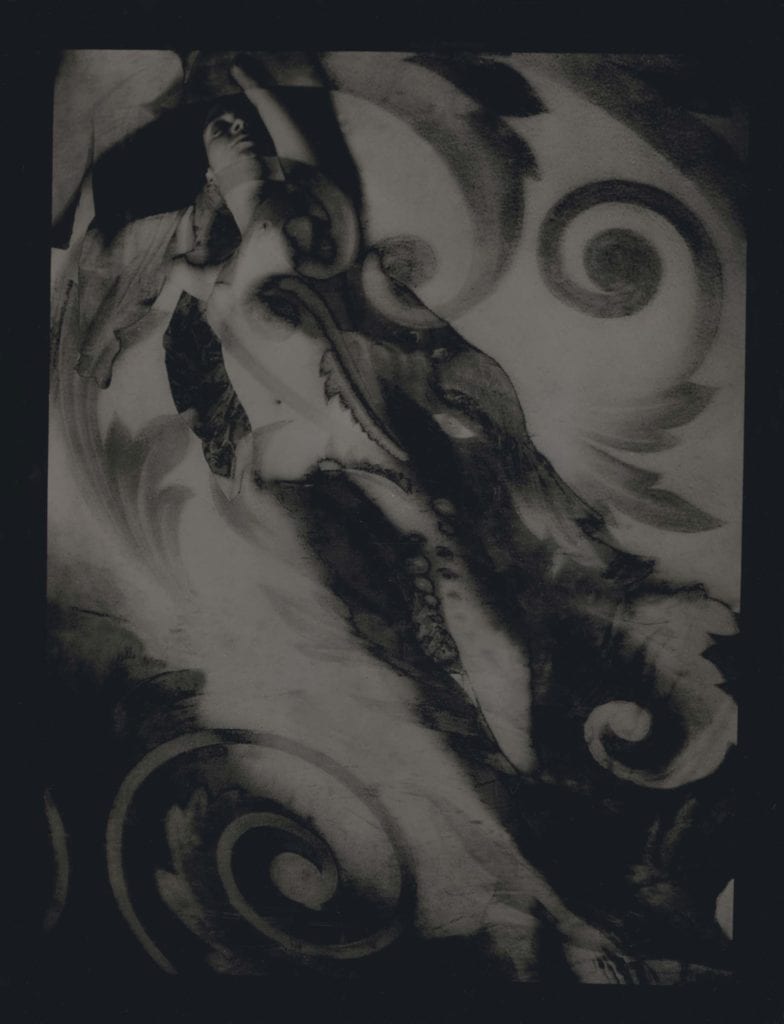

NM: You have said the poem Dear Master was singularly important in choosing the female imagery in this book. Why was this poem so important to you?

JS: The Dear Master poem is to me one of her most beautiful. She writes to a lover who is far away and tells him to remember her in the most beautiful metaphors , all taken from the nature around him – her voice in the wind, and the brook, a songbird singing her pain, a lofty crag, a wounded deer finding a cool stream , her soul in the clear sky etc.

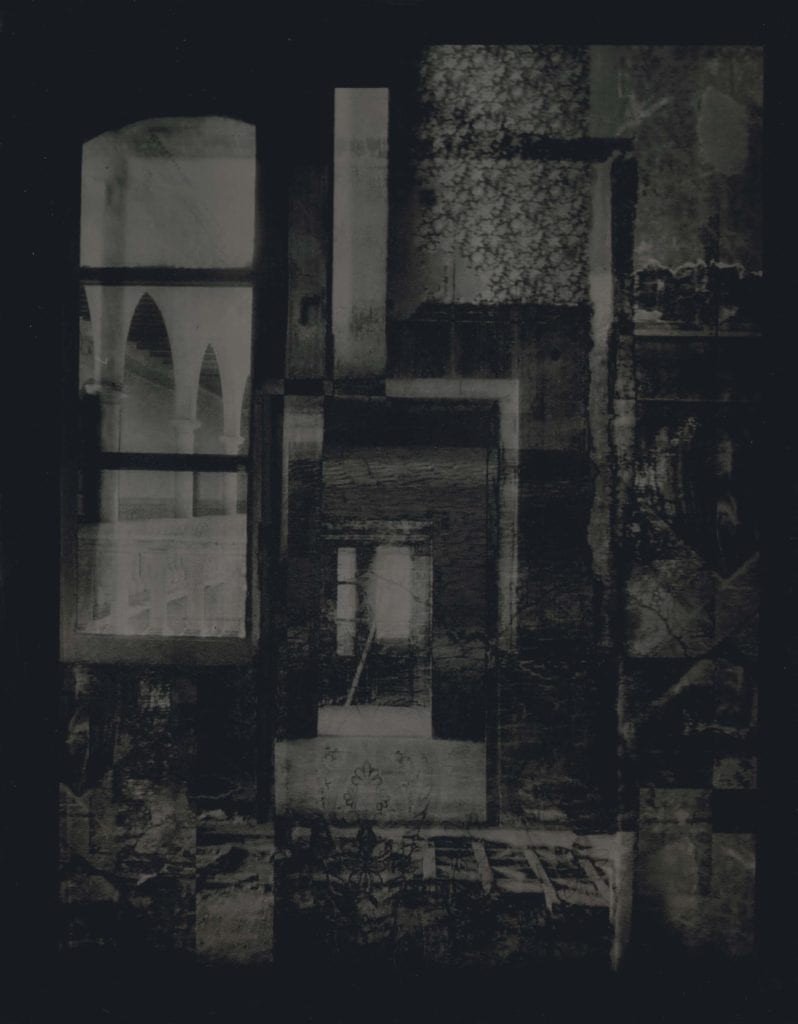

NM: Your books are works of art. Tell us about the process of designing the book, choosing the binding, the paper, the printer – it’s so obvious that there is an inordinate amount of care put into each one.

JS: Putting my books together is truly a collaborative process. I work always with the same people – Jennifer Shaw for printing, Jacqueline Miro for designing and Small Editions for binding and putting it all together.

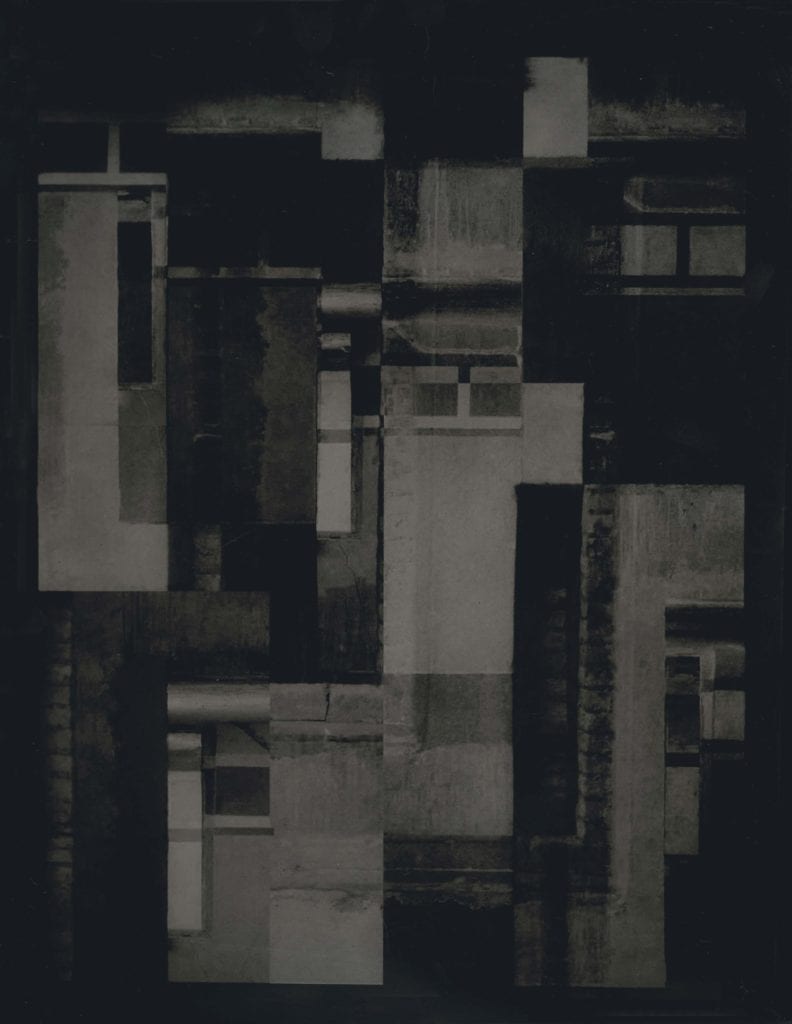

I usually have only some vague idea for the cover that Jacqueline takes up and runs with. We are doing 2 different editions of each book – one where all the prints are original gravures on Japanese hand made paper and we design a box for it and only make 6 copies – more like a bound portfolio. Then we do a less expensive trade edition of 500 so that we can reach a wider audience.

NM: I have loved getting to know your photography and your story over the past few years. You’re inspiring and a bit intimidating at the same time! What advice do you have to offer younger photographers today? What interests you about contemporary photographers these days?

JS: The only advice I have for young photographers is to stay true to yourself which can be really difficult since there are a lot of opportunities to be a flash in the pan in one way or another. On the bright side I see contemporary photographers working in every kind of process from tintypes to digital and all in between which I love. And I also love that a lot of photographers are telling us not only ‘this is what I saw’ but also ‘this is how I feel about it’. Bravo!~r

www.josephinesacabo.com

www.lunapress.com

Nancy McCrary

Nancy is the Publisher and Founding Editor of South x Southeast photomagazine. She is also the Director of South x Southeast Workshops, and Director of South x Southeast Photogallery. She resides on her farm in Georgia with 4 hounds where she shoots only pictures.