This A-2 jacket belonged to Captain Stephen M. Hoza of the 94th Bomb Group. He married his sweetheart Delores after the war, and passed away in 2010. The religious icon hastily sewn into the jacket liner caused me to realize that even Captains prayed during their hazardous missions. Courtesy of the Smithsonian National Air & Space Museum.

Genesis

Ideas pop into my head all the time, and sometimes they just won’t let go. You know the kind…they sit in the back of your mind…percolating…like one of those old fashioned coffee makers. The brown liquid just keeps bubbling and splashing around in the glass knob, until the heat is turned off. Only…the idea never turns off. So it becomes a part of one’s conscious thinking…which means it’s time to start planning, exploring, and examining the possibilities. Such was the case when a project photographing World War II “bomber jackets” was contemplated.

Inspiration comes in many forms and mine came from a series of antique motorcycle jacket photographs seen several years ago, created by Dan Winters. A long-time film devotee, he photographed them on a white lightbox, shot from overhead with a 4×5 camera. They were beautiful too, in their simplicity, their “grunginess,” and their diversity. While the technique is not new, the subject matter was. (As an aside, Albert Watson created images using the same method many years ago, photographing artifacts from all over the world, including Elvis’s pistol, an astronaut glove, fetishes from Morocco…). Since childhood, uniforms and military history have been a personal fascination. My dad was a career soldier, a Green Beret most of that time, until a parachute jump injury left him one jump away from being a permanent cripple. Growing up in that environment it was common to see soldiers on post, wearing all sorts of uniforms. Fatigues, “Class A” uniforms for parades and “Dress Blues” for formal events are all deeply rooted in function and military tradition. So it is with the A-2 flight jacket, and the M422 jacket Naval aviators wore in WWII.

The back side of SSG Clement’s jacket. “Miss N-U” was the name of his aircraft. While considered pretty tame by today’s standards, many jackets that sported scantily clad women were not worn after the war in the serviceman’s home town. It just wasn’t done, and because of that unspoken moral taboo many jackets survived, as they were hidden way for decades in forgotten closets.

Part of my interest in photographing these jackets is that not only are they military artifacts, but they largely spawned a new art form. While painting on the jackets was officially discouraged, most (if not all) commanders largely ignored that mindset. It was thought that “these guys could be gone tomorrow,” so let ‘em paint whatever they want on their jackets. It was good for morale, as the men could “individualize” the artwork on their jackets, linking it to their particular aircraft. They were a “crew,” and very much wanted to demonstrate that. Early on in the war (in 1942, on into 1943), there were no “mission quotas” to reach before one could go home, and casualties (killed, wounded, or captured) were as high as 70% in the Eighth Air Force flying out of England. Quickly it became a serious mental health issue, and the unit flight surgeons began noticing a drop in morale and performance as missions increased. Airmen experienced what is now called PTSD (Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder) in significant numbers, and keeping enough qualified/ experienced crewmen together became a serious challenge, affecting officers and enlisted men alike. While the jackets were merely leather tokens, it gave the men an identity and bond common only to them. Worn with fierce pride, many who have lost their jackets to kids, wives, deterioration, and/or life-events now greatly regret they no longer possess their original jacket. Most of the jackets were decorated with enamel or oil-based paints (sometimes airplane paint too!) , and were often painted by fellow soldiers who had artistic talents, in exchange for a six-pack of beer or a carton of cigarettes. During the war, several Walt Disney artists were drafted and unhappily ended up painting jackets and nose art on aircraft for much less money than they were making as civilians. Perhaps also not surprising, “cottage industries” sprung up wherever GI’s were stationed, which included artists who would paint a jacket for a fee, as in England, Italy, China, north Africa, and India. I’m sure it occurred elsewhere too, knowing the nature of economics around military bases. The jackets sported all sorts of symbology, which typically included the number of missions flown, depicted by bombs. On the left front of the jackets was most often the unit crest, with the owner’s name embossed or written on a small strip of brown leather. Officers wore rank on the epaulets, whereas enlisted men typically did not have any rank insignia. The back side, being of one-piece leather, was a perfect canvas for an artist’s expression. The multitude of designs and colors created is mind-boggling, and is a testament to their artistic ingenuity. Other symbols were used too, such as swastikas to signify the number of enemy aircraft shot down. Sometimes the mission target was inscribed on the bomb, especially for memorable missions that were lengthy, significant, or were exceptionally hazardous. Upwards of 750,000 jackets were manufactured, but the exact number is unknown. There were up to 18 different suppliers in the US., with jackets also made in England, Australia, and elsewhere, using the approved pattern. Many non-aviators wanted one too, and it was common to trade them with tankers, infantrymen, and others. Extremely popular, it came as a surprise when Gen. Hap Arnold cancelled the contract for A-2 jackets in 1943, as he wanted something “better” for the crews to wear. They continued to be issued until stocks were exhausted, and if you had one that had been lost or damaged, a replacement could be issued as well. They remained highly prized by new airmen after the war and were often sought after in thrift shops and army surplus stores. Perhaps not surprisingly, I’ve heard first-hand from an Eighth Air Force veteran that if a crewman didn’t return from a mission, often the first thing “liberated” from his belongings was his flight jacket. Such is life in the military… Original A-2 jackets from this era are now highly collectable. It is fairly common to find them on E-Bay, often going for several thousand dollars. In the late 1970‘s and into the ’80’s, Japanese collectors became very passionate about obtaining A-2 jackets, and a jacket in pristine condition could fetch upwards of $20,000. It was about this time too that theft became a problem. Jackets from the Smithsonian National Air & Space Museum (NASM) were stolen, as was Gen. Douglas McArthur’s jacket from a small museum in Virginia. Since jackets at the Smithsonian become US government property once assessed into their collection, the FBI was called in to investigate. My understanding is that none were ever recovered, and the case remains open. Speaking of the NASM, it was my privilege to photograph 13 jackets at the Udvar-Hazy Center in the summer of 2015, as well as 7 jackets at the National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, Florida. Initially, the goal was to photograph 50 jackets, and to date 63 have been photographed. Now that the project has gained a bit of attention, jackets continue to appear almost daily, and for the time being , I continue to seek out opportunities to photograph them. Since the project began over three years ago, it has become increasingly apparent that the stories surrounding the sacrifice these men freely offered to their country (and the world) should be the central theme of the book. To that end, as much information as possible regarding service records, units, dates, and so on is being researched. A real treasure trove are the logbooks and personal journals that were kept during the war. Other items of interest are being photographed too, which should help tell the story of time away from home, close calls, and friends lost. When possible, portraits of surviving air crew veterans are being created, and their stories recorded. Photographically, the setup is straightforward. Placed on the floor, strip lights (1’x4’) on the left and right light a 4’x4’ white plexiglas from underneath, so that a solid background isolates the jacket in a field of white. Two 1’x4‘ plywood pieces support the plex at the top and bottom side, with a small post placed in the center, so the heavy plexiglas doesn’t sag. A Profoto “beauty dish” with a grid is used to light the top surface of the jacket, with white cards on three sides adding additional fill light. Shooting from a six-foot ladder looking down on the subject completes the lighting arrangement. This setup travels well too, aside from the large plexiglas sheet, which fits in the van easily. About 45 minutes is needed to set up, in a space about 12 feet square. So far, jackets have been shot in storage rooms, a public library office, and in my basement. Both sides of the jacket are photographed, even if they have no artwork on the back. Using a Phase One 645DF medium-format camera, coupled with a Leaf Credo 60 digital back, files are created that once opened in Photoshop are 350 mb (16 bit). The logic behind using this camera is that fine art prints will be offered for sale, and a traveling exhibition is planned of life-sized prints. Two 30×40 inch test prints reveal spectacular detail, thanks to the file size and the sharpness of the Schneider 80mm 2.8 LS lens. While shooting, the camera is tethered to a Macbook Pro, and using Capture One software, the files can be viewed in about 3 seconds with any adjustments made as needed. This setup actually speeds the process along, as it’s easy to determine when the shot is satisfactory, and allows others to see the result.

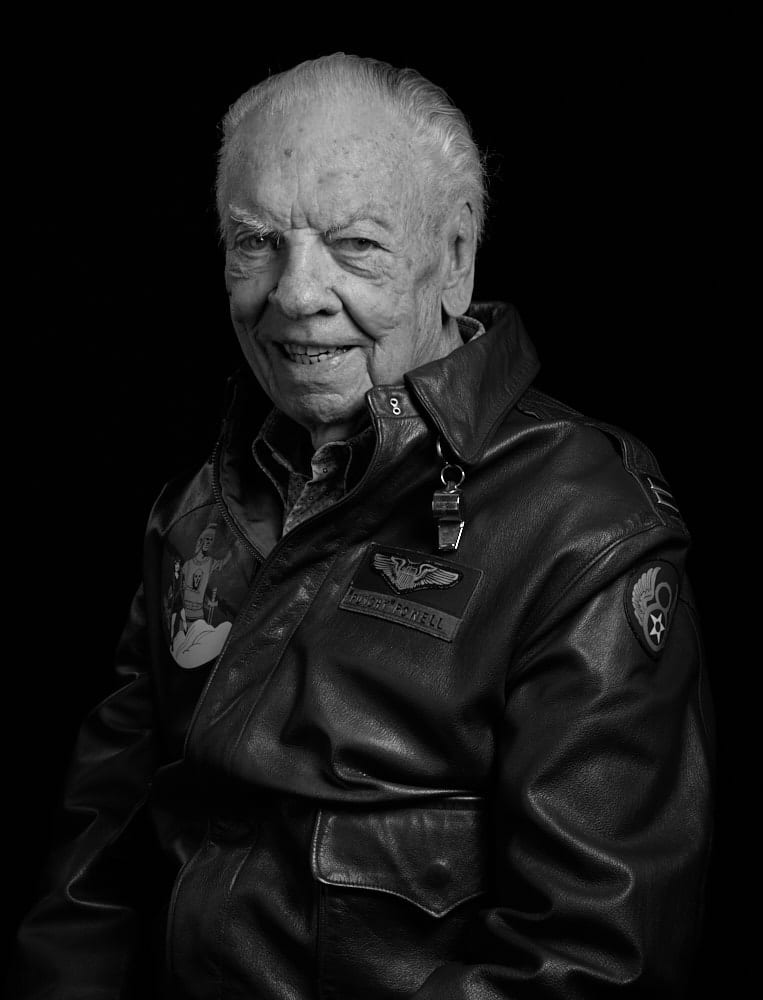

SSG Robert M. Mitchell, Jr. wore this jacket on all of his 38 missions as a B-17 ball-turret gunner. A member of the 544th Bomb Squadron, 384th Bomb Group, he designed the ball-turret logo on the front of his jacket. Coming from a family with a long tradition of military service, his father (a World War One veteran ) had a few words for him, prior to his departure for the service. “I want you to come back one of two ways…proudly wearing the uniform of our country, or in a flag-draped box…”.Mr. Mitchell passed away about a month after this image was created, in May, 2015. A video interview with Mr. Mitchell was created the same day by my friend Michael Schwarz, a former Atlanta Journal Constitution (and Pulitzer Prize nominated) photographer.

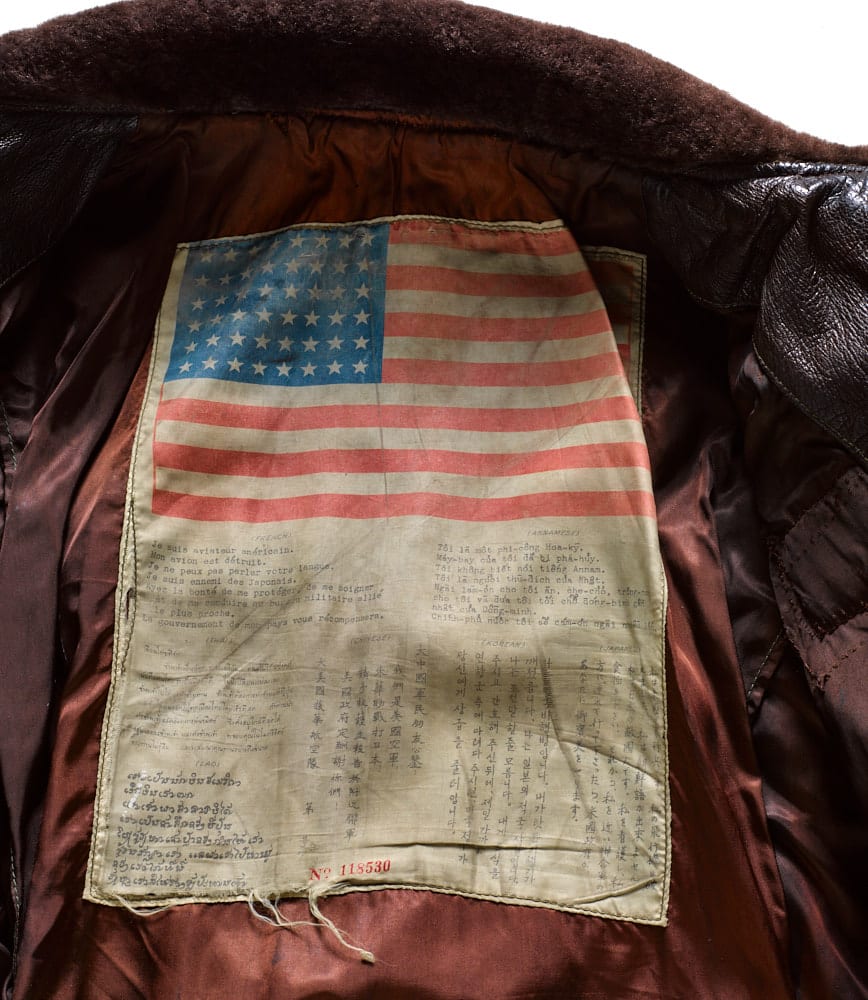

A “blood chit” inside the jacket of Marine Lt. General R.P. Keller, one-time commander of the famed “Black Sheep” Squadron. Worn largely by aircrew in the China-Burma-India (CBI) Theatre of operations, it was a message printed in all of the languages they might encounter if brought down in enemy territory. It basically says “I’m an American airman, here in your country fighting the Japanese. Please provide food and shelter and you’ll be rewarded.”Still in use today, “chit” is an Indian word the British picked up, and means “ticket.” Notice the red number at the bottom. If the person claiming to have rendered aid to an airman couldn’t supply the number, no reward was given. Courtesy of the National Naval Aviation Museum, Pensacola, Florida.

Without a word, I immediately showed him this picture on my iPad, and said “This Walter Thomason, ofUncle Tom’s Cabin?” “Yes!” was the excited answer, and we both got goose bumps just thinking about the odds of finding a connection to another member of the same crew.

The second jacket has now been photographed too, as they will appear side by side in the book. Only at Oshkosh!

B-17 waist gunner SSG Harvey Brundage carved these models from broken pieces of plexiglas bomber windshields in his spare time while in England. A member of the 401st Bomb Squadron, 91st Bomb Group, he completed 30 missions.

Always talented with his hands, he built a house in Iowa for his family after his return from the war.

Lt. (jg) Leroy Robinson flew F6F “Hellcats” as a member of the Navy’s VF-2 “Rippers.” Part of the USSHornet air wing, they shot down or destroyed 55 enemy aircraft, sunk 27 ships, probably sunk 22 more, and damaged more than 128 in the month of September, 1944. VF-2 became the top fighter squadron in the Pacific with more total victories and more aces than any other fighter squadron. Of the 50 pilots on board, 27 were confirmed aces, including Robinson. Decorated five times with the Distinguished Flying Cross, he also flew in the Korean conflict.

He later had a 32 year career with Delta Air Lines, retiring to Tignall, Georgia, living in the family farm house which was built just prior to the civil war. He passed away in the spring of 2016. He is shown here wearing a replica of his original jacket.

Captain Everett Graves was a Humboldt, TN. native, and completed 50 missions with the 762nd Squadron (the Black Panthers), of the 460th Bomb Group, flying B-24 Liberators out of Spinazzola, Italy. Overseas from 25 January, 1944 until 21 November, 1944 he was wounded on his 9th mission by flak in his neck and shoulder, which narrowly missed his spinal cord. After 4 weeks in the hospital, he returned to flying duty, completing his remaining 41 missions. He was awarded the Air Medal with 3 Oak Leaf Clusters, the Distinguished Flying Cross w/1st OLC, the Purple Heart, and other Theatre ribbons.

An excerpt from his diary reads: “8/7 Monday. Group hit Blechhammer, North, today. I flew with Van’s crew. Had #2 engine shot out over target, ball turret out, left waist and left tail guns out. Attacked by ME-109’s (German fighters) as we were straggling. We got back somehow. Hydraulic system shot out, no brakes, ran off runway between two parked ships, jumped 3 or 4 ditches, and came to rest 300 yards off the runway in a wheat field. No one hurt. Ship full of holes. Amann and Hunter MIA (missing in action). Flak intense, heavy and accurate. Had P-51 and P-38 fighter cover to the target and during withdrawal. It was a tough mission. Number 3 engine cut out, got it back in, very low on gas. 1150 nautical miles. Had 2 letters from Evelyn, and 1 from home and 1 from Mammy. Very tired and worn out tonight. Group claims 8 fighters down…”

He was promoted to Captain on October 23rd, 1944, and finished his last mission the next day.

Lt. General Jimmy Doolittle and Lt. Ernest A. Erickson in June, 1944 at Horham Airfield, England.

They are standing beneath the nose of a B-17G named “Lady of Fortune,” and Lt. Erickson is wearing the jacket photographed for this book.

General Doolittle was famous for the raid on Tokyo in early 1942, for which he was awarded the Medal of Honor by President Roosevelt. Later, he was the commander of the Eighth Air Force.

Lt. Ernest Anders Erickson flew 35 missions as a B-17 pilot with the 95th Bomb Group (Heavy) out of Horham Airfield, England, from March through December, 1944. “Lili of the Lamplight” was his usual ride into battle.

Their aircraft was so named because he and his crew saw Marlene Dietrich perform a USO show, which quite impressed Lt. Erickson, and because the co-pilot’s wife was named Lily.

The phrase was actually lifted from a then-popular German love song sung by Dietrich, originally written as a poem in 1915, and set to music in 1937. During the war, it became wildly popular with soldiers on both sides, and was frequently used to end Radio Belgrade’s broadcast each night at 10pm.

Aero Leather Clothing Company in Beacon, New York was the manufacturer of this jacket. The contract date was 25 May, 1942, for 50,000 jackets.

It was quite common for names to be stenciled inside the jackets, as it was thought that “the Army would not want them back.” Others removed the tag, for the same reason.

It should be remembered that at the time, zippers were a relatively new technology for garments. This jacket is a size 40, which is about average for the jackets I’ve seen. Also, be aware that a size 40 then is not the same as a size 40 now. People were generally smaller in those days, and airmen were generally small- framed, so they could fit into the snugly built aircraft.

The jacket was lent courtesy of his son Mark, a fine-art painter in Oakland, California. His dad died on 7 June, 2013 at age 90, and is missed terribly by his family.

In military lingo, an “ace” is someone who has shot down five or more enemy aircraft. Navy Captain Stanley W. “Swede” Vejtasa was an ace twice over, once shooting down 7 aircraft in a single day during WWII, which earned him a Medal of Honor nomination.

Already a Navy pilot when the war began, in the Pacific he flew from the USS Yorktown, and the USS Enterprise, and participated in the Battle of the Coral Sea, the Solomon Islands, the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands, and supported US Marines on Guadalcanal.

After the war, he held a variety of assignments and participated in the Korean War as the air officer aboard the USS Essex, and later witnessed the development of jet aircraft.

In November, 1962, he took command of the one of the Navy’s newest carriers, the USS Constellation (CVA 64), after which he became the commander of Naval Air Station Miramar, otherwise known as “Fighter Town,” made famous in the movie “Top Gun.”

When he retired in 1970, his log books showed 9,000 flight hours and 700 carrier traps (landings). Courtesy of the National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, Florida.

##

Should you know of anyone that has an original A-2 (preferably with artwork on both sides), please consider putting us in contact. Condition is irrelevant, as I want to show them “as is.” Prints are being provided at no cost to the owner, or in the case of the museums, digital files for their archives.Several jackets have been shipped to me, photographed, and returned without incident, but there are those who understandably would rather not entrust such family heirloom’s to the vagaries of shipping companies. One mother/daughter tandem drove from Iowa to Atlanta, bringing a jacket and other artifacts. This level of commitment floored me, but such is the nature of this project and the passions it has aroused. Most of the jackets photographed so far have come from private owners, which has proven to be the most reliable source of information as well.To date, the project has been self-financed, but I’m actively seeking corporate partnerships to help sponsor the book’s production costs. While the amount is not insignificant, it could be a wonderful vehicle to convey a company’s values and support of our veterans and military aviation history in general. To discuss sponsorship opportunities I can be reached at (404) 245-2411 in Atlanta, or via email at john@aerographs.com.

John Slemp:

Born in Japan, John Slemp was a world traveler before he was a teen. After attending college on an academic scholarship, he served in the US Army stationed in Germany, and out of curiosity spent many hours visiting well-known museums throughout Europe. Little did he know that he was preparing for a life in commercial photography, and the world’s best art was a spellbinding tutor.Fast forward twenty-plus years, and his wide-ranging photography experience allows him to create environmental still life, portraits, and lifestyle images, specializing in aviation. He’s a recently licensed FAA drone pilot, which has been incorporated into new assignment work as well.Light, shape, and composition are the tools used to create images for a wide variety of editorial, corporate, and advertising clients worldwide. Easy to work with, his goal is to create the best images possible for each assignment. A great sense of humor is an added plus, which keeps everyone on set loose and lively.As an aside, he’s a big fan of dogs, fly fishing, and a good cheeseburger. Oddly, he likes cutting the grass too, as it offers time to think..and we cut a lot of grass in the South.His work has won several industry awards, including twice being selected for the Best of ASMP competition. His fine art work hangs in a number of private and public collections, which he continues to actively exhibit.

Nancy McCrary

Nancy is the Publisher and Founding Editor of South x Southeast photomagazine. She is also the Director of South x Southeast Workshops, and Director of South x Southeast Photogallery. She resides on her farm in Georgia with 4 hounds where she shoots only pictures.